The technology behind the Gjellestad ship find

With the help of newly developed motorised georadar systems, NIKU's archaeologists did some major discoveries at Gjellestad - including a Viking Ship. But how does the technology work and what will happen next?

The archaeologists were able to see five long houses, at least 10 burial mounds and what is probably a Viking. The find has caught worldwide media attention.

Because of this spectacular finds the technology behind the discovery are also getting more attention.

The motorised georadar system can be compared to an echo sounder that sends a signal down the ground with a reflex. Based on these signals, archaeologists map out areas that stand out from its surroundings – so-called anomalies.

– An anomaly is simply something that differs from what lies around. At Gjellestad, one of the these was a clear ship-shaped anomaly centered in the middle of a burial mound, says Lars Gustavsen, archaeologist at the Norwegian Institute of Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU)

The georadarsystem used was a MIRA from Guideline Geo and further developed for archaeological purposes by the International Research Institute, Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archeological Prospection and Virtual Archeology (LBI). LBI has been a partner organization of NIKU since 2010.

Read more about the Department of Digital Archeology here.

Technology and interpretation

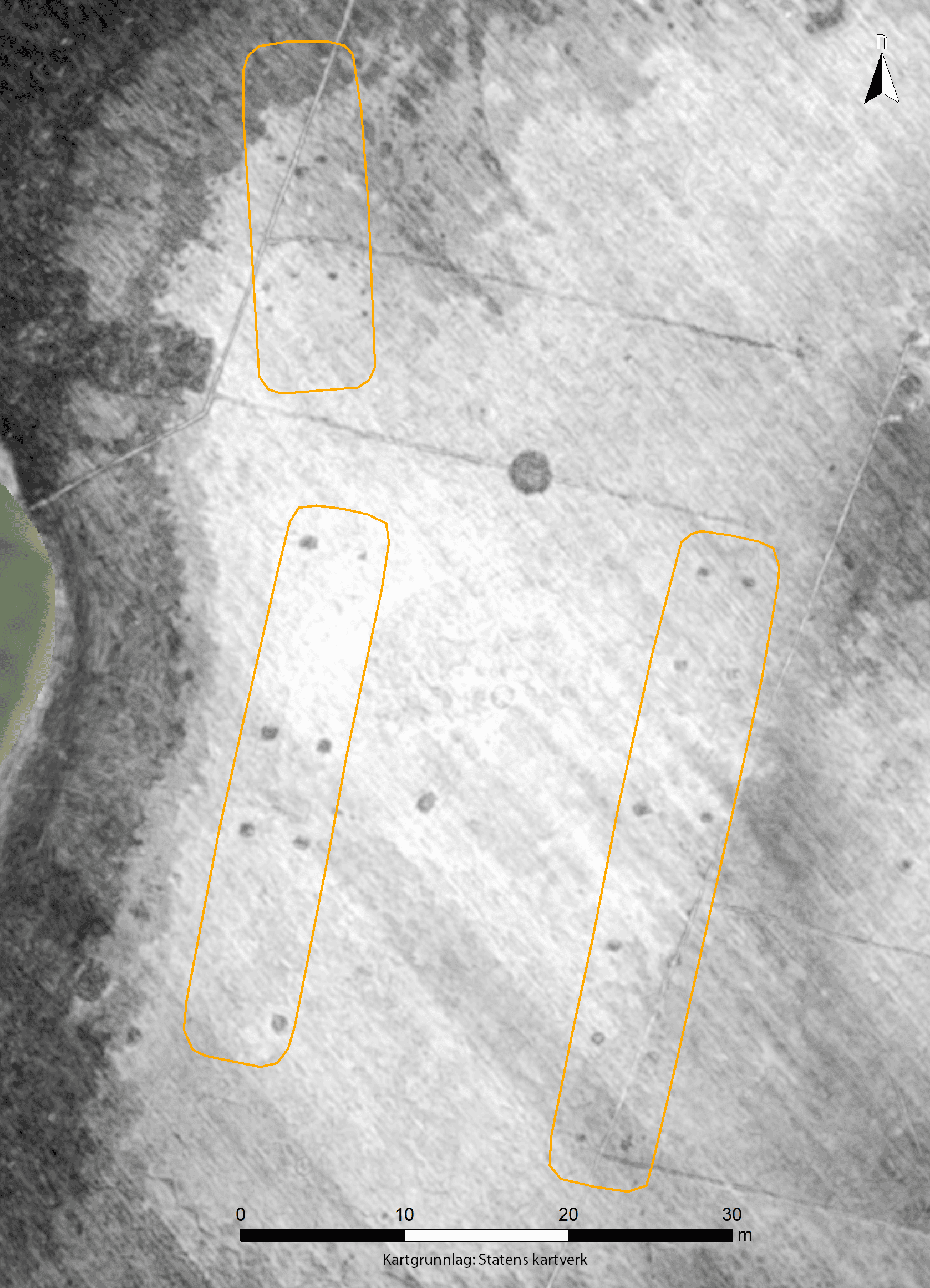

The georadar sends out radar signals that descend through the ground layers, when they encounter resistance, parts or the whole signal are reflected to a receiver. The result will be gray scale images for every 5 cm down in the soil layers.

– The bright parts of the image are areas where the signal penetrates the underground evenly and just disappears into the underground. The dark parts are where the signal is reflected back due to changes in layering or substructures. When we put the individual performance images together for an animation, the anomalies emerge in an easy-to-understand way, says archaeologist at NIKU, Erich Nau

Further, the archaeologists interpret the results to assess whether they may represent archaeological structures underground. This way you can get an idea on where it might be worth doing closer surveys.

Georadar results are conditional

How good these results will be depends on several factors. Both soil, moisture in the soil and depth have something to say, as are modern structures and other disturbances in the area.

At Gjellestad, the archaeologists have two datasets. A smaller part of the area was studied already in April when the ground was relatively wet. A complete dataset was collected in August when the ground was dry. The difference in moisture in the subsoil is also reflected in the results according to Gustavsen and Nau.

– In the data set from April when it was very wet, we see more of what we think is the boat’s keel. We saw less of it in August when it was dry. And we think it’s the different levels of moisture in what we think is wood that comes into play here, “says Nau.

What happens next at Gjellestad?

The archaeologists from NIKU now want to carry out more investigations in the area. In addition to further geophysic surveys, they will also employ a range of non-invasive digital methods.

The GPR is most responsive to what is known as dielectric permittivity, a property of the soil and the archaeological structures beneath the ground.

– By using other geophysical methods, such as geomagnetism or electromagnetic induction, it will be possible to gather further information about the magnetic and electrical properties of the subsurface. This could potentially provide more and different information about the preservation conditions of the ship find and the location of iron objects, says Nau.

Nau and Gustavsen want to learn as much as possible through non-invasive methods before any potential excavation takes place in the area.

– This can be compared to non-invasive medical examinations, such as X-rays, before a surgeon begins the actual operation.

The Directorate for Cultural Heritage has compensated the landowner and farmer Olav Jellestad for one year, allowing more investigations to be conducted at Viksletta.